CrystalFormer-CSP: “Fast Thinking” and “Slow Thinking” for Crystal Structure Prediction

Given a chemical formula, for example Cu₁₂Sb₄S₁₃, how should the atoms be arranged in space in order to form a stable crystal? This is the problem of crystal structure prediction (Crystal Structure Prediction, CSP), one of the fundamental challenges in materials science research. Recently, the Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences released CrystalFormer-CSP to the DeepModeling community, adopting a strategy that combines “fast thinking” and “slow thinking” to address this challenge.

Fast Thinking and Slow Thinking

The Nobel Prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman proposed a classic theory that human thinking is divided into two systems. System 1 (“fast thinking”) relies on intuition and experience, responds rapidly, but is prone to errors. For example, when seeing “1 + 1”, we can almost give the answer without thinking. System 2 (“slow thinking”), by contrast, relies on logical reasoning, operates more slowly, but produces reliable results; when solving a problem in advanced mathematics, one must carefully work through each step. CrystalFormer-CSP puts this idea into practice in the task of crystal structure prediction: a generative model is used to quickly “guess” candidate structures, and physical calculations are then used to slowly “verify” their stability.

System 1: Rapid Generation

CrystalFormer is a pre-trained crystal generative model that plays the role of System 1. By compressing databases of stable crystals, it learns a form of “chemical intuition”: which space groups, Wyckoff positions, and coordination relationships are more likely to form stable crystal structures. Given a chemical formula as input, the model can rapidly generate a large number of candidate structures. Its advantage lies in its speed and broad coverage, but the generation process does not rely on concepts of energy or force at all. Just like human intuition, it is fast, but not necessarily accurate.

System 2: Physical Verification

System 2 is responsible for energy relaxation and ranking. For each candidate structure, a machine-learning force field continuously adjusts atomic positions and lattice parameters, allowing the structure to “slide” along the energy surface toward lower energy. Ultimately, the stability of the structure is evaluated using the convex hull energy (E_hull). This stage follows physical principles and answers the core question: from an energetic perspective, can this structure exist stably? Its advantage is physical reliability, but the cost is slower computation.

Reinforcement Learning: Letting Slow Thinking Shape Fast Thinking

The “fast thinking and slow thinking” of crystal structure prediction is not merely an analogy. Based on the above understanding, this work further adopts a technical framework of reinforcement fine-tuning with large language models to continuously improve the system.

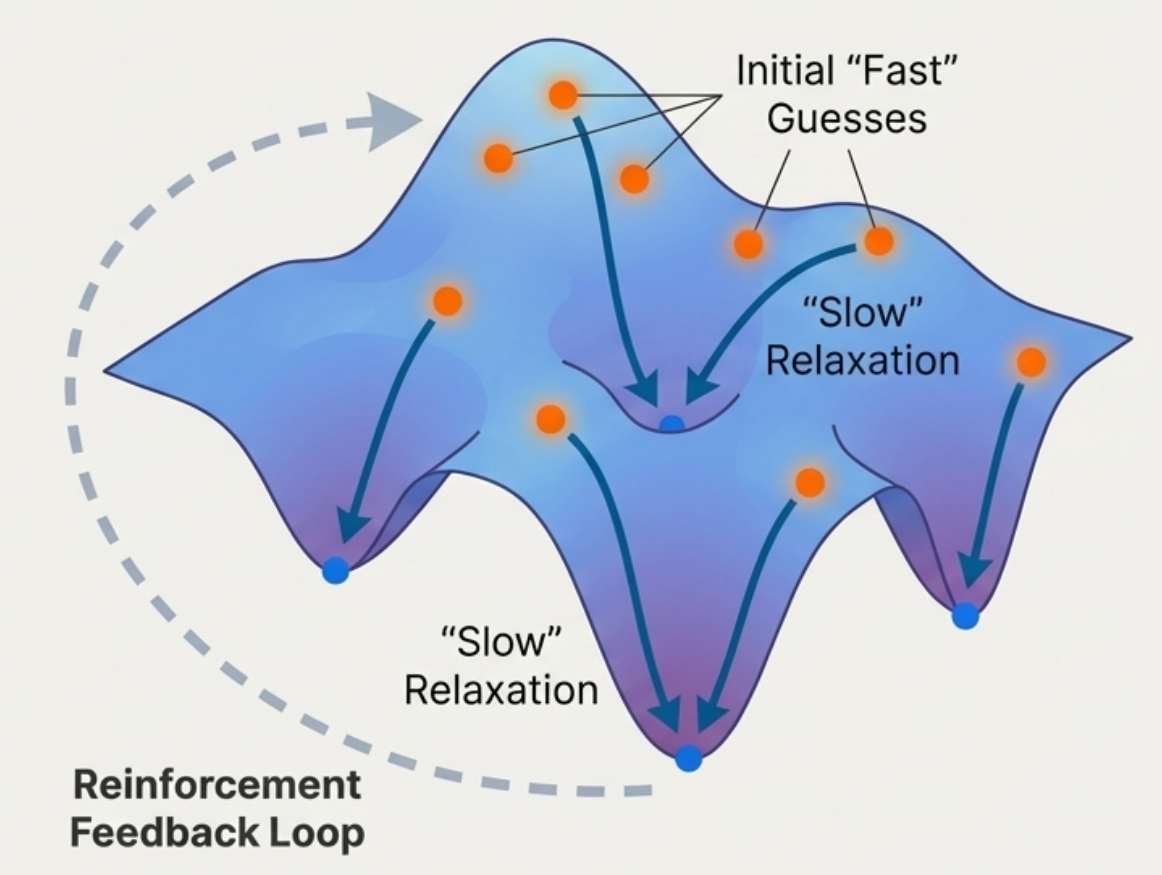

As shown in the figure below: on the blue potential energy surface, the orange points represent the initial guesses rapidly generated by System 1, and the dark blue arrows indicate the relaxation process of System 2, where the structures “slide” along the surface toward local minima (blue points). The gray dashed lines on the left represent the feedback loop of reinforcement learning: the energy information after relaxation is fed back to the generative model via policy gradient algorithms, enabling System 1 to no longer merely imitate training data, but to gradually learn to generate structures that are more physically stable.

The core challenge of crystal structure prediction lies in the need to find structures with sufficiently low energy while avoiding being trapped in a single configuration and missing other potentially stable phases. The reinforcement learning framework is naturally suited to this problem. By adjusting the relative weights of the energy term and the entropy term in the reward function, one can flexibly balance “energy minimization” and “structural diversity”. Experimental results show that for crystals that were previously predicted unsuccessfully, reinforcement fine-tuning leads to a significant improvement in success rate.

Why Does This Work?

Directly searching for the lowest-energy structure in atomic coordinate space means dealing with a rugged, high-dimensional potential energy surface full of local minima. One can imagine searching for the lowest point in a mountainous landscape: it is easy to get trapped in a small valley and fail to escape. Reinforcement learning changes the nature of the search. Instead of moving atoms one by one, it adjusts the “generation rules” themselves. In the model parameter space, a small update can simultaneously affect multiple atoms and symmetry sites, resulting in a non-local, highly structured search. This makes the method often more efficient than direct searches in configuration space when dealing with complex crystal structures.

Open Source and Usage

CrystalFormer-CSP is open-sourced under the Apache-2.0 license in the DeepModeling community:

CrystalFormer-CSP

The project includes models trained on the Alex20s dataset, and also provides a Google Colab version as well as MCP tools that support integration with large language models. If you encounter any issues during use, feedback is welcome via GitHub Issues.

Future Directions

The current framework focuses on stable structures at zero temperature and ambient pressure. In the future, it can be extended to finite-temperature and high-pressure conditions, moving from answering “what is the most stable structure?” to “under what conditions does a particular structure appear?”. At present, the method is mainly applicable to inorganic crystals; future work may explore extensions to organic crystals, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), and disordered systems.

Takeaways

- ⚡ System 1: fast generation, chemical intuition, pattern matching

- 🐢 System 2: energy calculation, physical constraints, slow but accurate

- 🔄 Reinforcement learning: allowing slow thinking to in turn shape fast thinking